a STORY OF RAISING QUESTIONS ABOUT AN ARTWORK

How do we know who the creator of an artwork is? It sounds like it should be a simple question, but its one that museums have to ask about our collections regularly.

At the Williamson, many items in our collection have been generously donated by supporters, patrons and benefactors. Particularly in the early years of collecting, records on provenance (how an artwork came to be owned by the donor and proof that it’s genuine) were not always well kept, or have not survived. This means that when we take another look at some objects, we have to call the attribution (who we’ve been told the creator is) into question.

Most of these mistakes are harmless, not deliberate. They occur most frequently in our collections of objects from around the world, where a traveller has been spun a tale to encourage them to splash their cash. Whilst many of our travelling donors have likely had an interest in the culture of the places they visit, there’s a difference between this and a specialist knowledge which might stop you being taken for a ride by vendors eager to sell ‘rare’ or ‘unique’ souvenirs.

A particular favourite example of this in our collections is the tale of this figure of the Egyptian god Bes. The Egyptology team from Liverpool University who produced this photogrammetry model of the piece were amused by the addition of his “hat” – a modern addition to an ancient figurine. Their best guess at the likely reason for this unusual addition was to make it seem even more unusual to the tourist audience.

Recently we believe we’ve uncovered another such story within our small collection of Japanese prints. According to our accession records, we have two works by Hokusai. One of the greatest master of the ukiyo-e printmaking tradition, Hokusai (1760-1849) is probably best known to Western audiences for his work The Great Wave Off Kanagawa (1831).

For modern Art and Art History students, studying at least a little of Hokusai’s work is commonplace. The opening of Japan’s borders in the 1850s and the arrival of ukiyo-e in Europe had a major impact on the development of art in Europe. Japanese prints were mass-produced in runs of thousands, so could be easily exported. Their striking graphic style and use of perspective, often quite different to that of traditional Western art, were a great source of inspiration to artists of the late 19th century, including Monet and Van Gogh – both of whom were known to directly copy various Japanese artworks.

So we don’t just know the names of famous artists, but have more knowledge of their work. This makes it much easier for us than it would have been for most Europeans a century ago to look at a print attributed to Hokusai and raise a sceptical eyebrow, when required – as in this case.

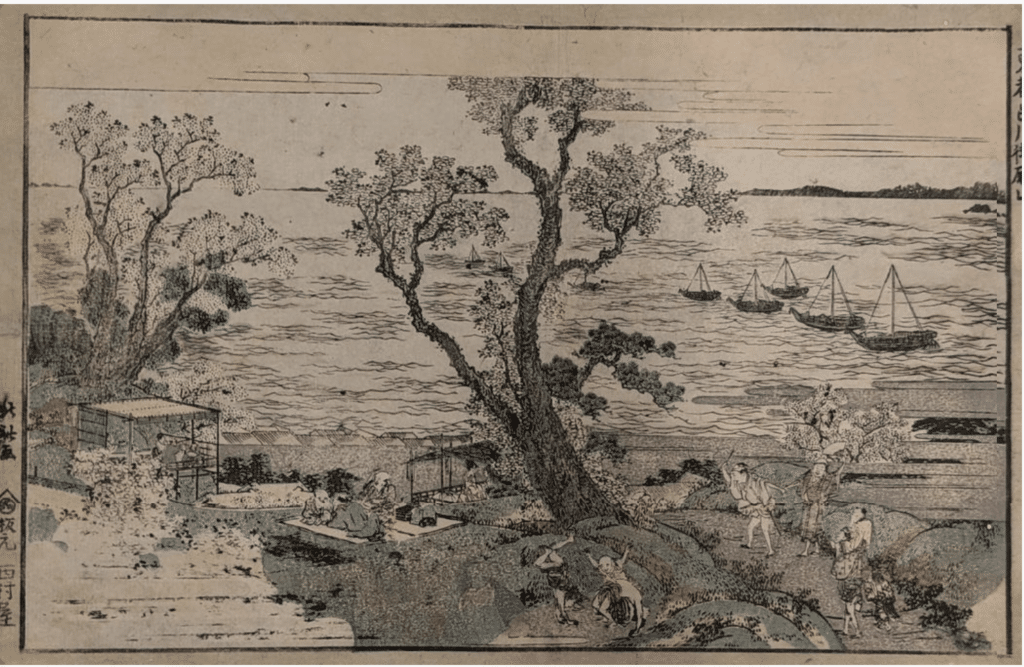

The reasons that we have begun to question the attribution to Hokusai of the work called Shinagawa at Cherry Blossom Time (above) are:

Style: although Hokusai did produce in different media and there are some similarities with other examples of his work, overall this comes across as too stiff for a typical Hokusai. This is particularly apparent in the human figures on the shore.

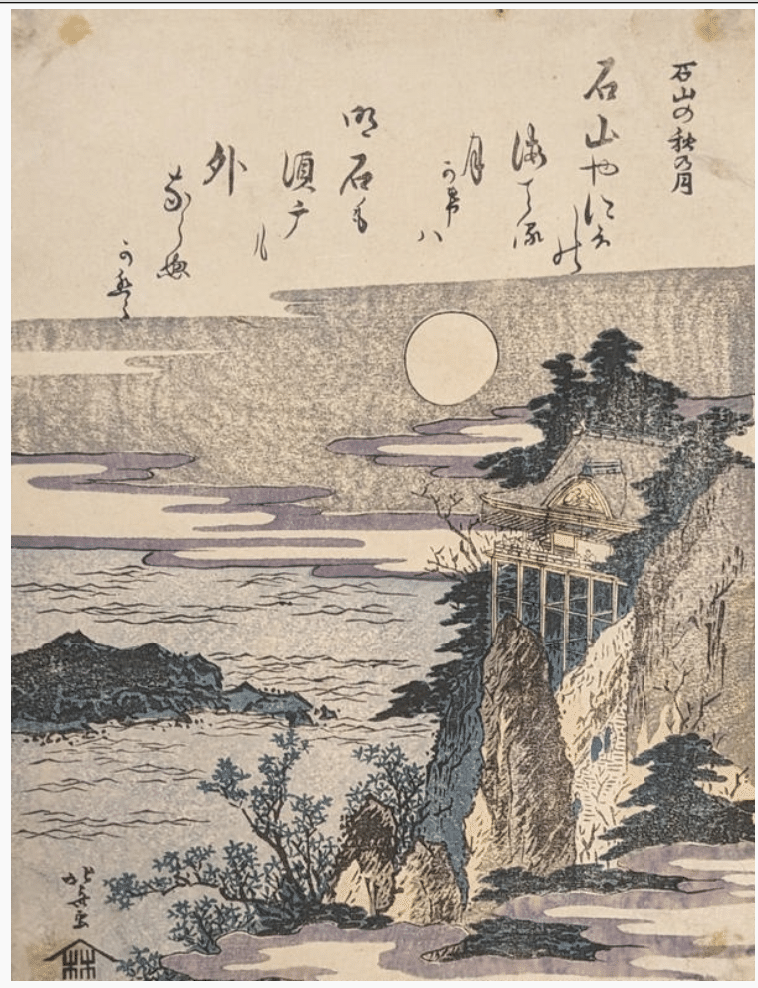

Text: In this work the text is confined to outside of a clearly delineated border. However Hokusai never kept such a distinction of space in his works. He often writes in the blank spaces of an image such as the sky, or directly next to a sketch. He often puts titles and inscriptions directly onto the work or in their own boxes. Another work in our collection, a print we know is a Hokusai The Omi Hakkei (Eight Famous Views of Lake Biwa) (right), is a great example of this. However, in our research to date we cannot find another example of text and image so distinctly occupying their own spaces in a work by Hokusai.

Reproduction: The prevalence of reproductions of ukiyo-e images helps greatly in research. There are, for example, approximately 100 copies of the original press of The Great Wave Off Kanagawa still on record from an original run of approximately 8000 , and even a brief search for most ukiyo-e reveals examples from other collections across the world. For this work, however, we can find no like examples, not even under other names.

For the time being we have changed its record in our collections database to “attributed to” Hokusai. With further research we hope to be able to discover more about the true origins of this work.